Episode 15

The Power of Pop-Up Exhibitions (with Robert Forloney)

Show Sponsor

Landslide Creative provides custom website design and development for museums who want to increase their engagement and connect with their visitors, donors, and volunteers. Stop fighting with your website and focus on growing your impact. Visit LandslideCreative.com to learn more.

Show Notes

About the Episode

Let’s explore the power and possibility of pop-ups: temporary or ephemeral museum-y experiences. I’m joined by Maryland Humanities’ Robert Forloney for a discussion about the Smithsonian’s traveling pop-up program, Museum on Main Street, and how short-term exhibitions allow for more play, creativity, and risk-taking.

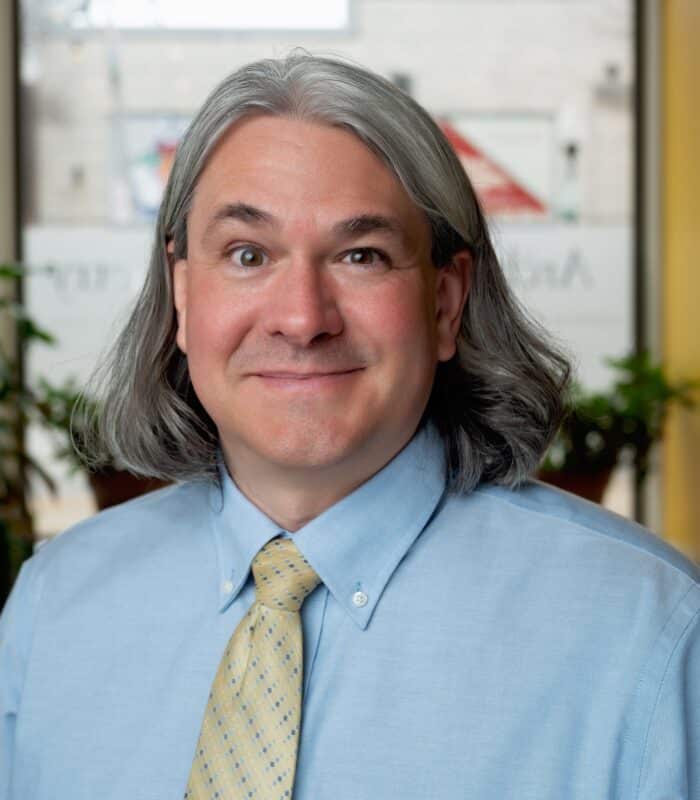

About our Guests

Robert Forloney is a Maryland Humanities’ Program Officer, Partnerships working with organizations to develop innovative programs and facilitate strategic planning. He currently oversees the Museum on Main Street collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution as well as the Regional Humanities Network across Maryland in this role. He has worked in the museum field for more than twenty years as an educator, administrator and consultant at institutions such the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Museum of the City of New York, American Museum of Natural History, the Museum of Modern Art and the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. In addition he has formally taught as a classroom teacher for the New York City Museum School as well as adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins University, Goucher College and the University of Delaware.

Links

SITES – Museum on Main Street (Main Website)

Smithsonian’s Stories from Main Street (MoMS Podcast)

WTM Ep 5: Public School/Museum Collaboration in Baltimore

Sparrows Point: An American Steel Story

“Women of Steel exhibit outside, free to public at Baltimore Museum of Industry” (WBALTV11, Oct 2020)

“When covid-19 shut down this Smithsonian museum, one exhibit came outside” (The Washington Post, Feb 2021)

Anacostia Community Museum – Men of Change: Taking it to the Streets

Transcript

Hannah Hethmon (Narration): Welcome back to We the Museum: a podcast for museum workers who want to form a more perfect institution.

I’m your host, Hannah Hethmon.

My very first podcast, back in 2017, was called Museum in Strange Places. The strange place in that case was Iceland. But I’ve always been interested in museums in strange places – exhibitions and displays outside the museum walls, in spaces where you wouldn’t normally expect to learn about art or history or culture.

I wanted to explore the possibilities of pop-ups, temporary or ephemeral museumy experiences. And I thought a great way to do that would be to focus in on the Smithsonian’s Museum on Main Street program, which has been innovating in this category for nearly 30 years as they bring modular exhibitions to small towns in America for six weeks at a time.

My guest today is Rob Forloney. Besides being very active in the museums and humanities spaces in Maryland generally, he is the Program Officer for Partnerships at Maryland Humanities. In that position, Rob helps run the Museum on Main Street program in this state.

Coming up, Rob and I get into the Museum on Main Street model and how state humanities organizations use it to generate even more pop-up exhibitions and programs. We’ll also take a look at how other institutions and community groups in this region are using the power of the pop-up to reach more people.

I should caveat this by saying Museum on Main Street has been one of my podcasting clients for the last few years. If you’re interested, that podcast is called Smithsonian’s Stories from Street. But they aren’t sponsoring this episode or anything; I’m just genuinely a big fan of the program.

But you know who is sponsoring this episode? Landslide Creative. Landslide Creative provides custom website design and development for museums and other nonprofits who want to increase their engagement and connect with their visitors, donors, and volunteers. With a custom website designed for the unique needs of your museum, you can stop fighting with your website and focus on growing your impact. Head over to LandslideCreative.com to learn more.

Hannah Hethmon: So can you tell me about Museum on Main Street and how it works from the state humanities perspective?

Rob Forloney: Yeah, so essentially it’s put together by SITES, which is the Smithsonian Institution’s Traveling Exhibition Service. And the idea behind this is there’s a core exhibition that the Smithsonian puts together around a particular topic or theme. It could be water, occupation, sports, whatever it might be, and it’s viewed through a national lens. So the Smithsonian creates a modular exhibit that travels around the country, and then in each particular state, the Humanities companion exhibitions and programming that is tied to the particular community itself. So that’s really what my role as a program officer is, helping the various local communities which are in rural areas develop their own pop-up exhibitions that are typically up for six weeks and that are tied to the overall theme, but really focus specifically on the values, the characteristics, the qualities, the history of their local community.

Hannah Hethmon: Can you describe some of the spaces that these exhibitions have been in Maryland and some of the creativity you’ve seen? We’re just gonna give like rapid fire, all the different ways that Museum on Main Street has kind of showed up in Maryland.

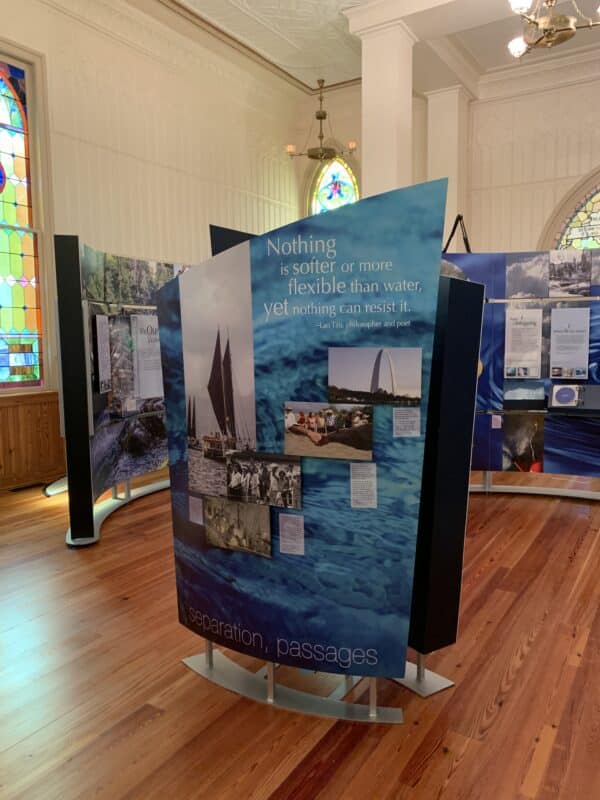

Rob Forloney: So essentially what’s really nice about it is it’s designed by sites in the Smithsonian to be a modular unit. It comes to us in a variety of different ways in crates, and we usually have about six different sections and segments. And what’s nice about it is that each individual segment can be exhibited on its own, so there doesn’t need to be a clear progression from start to finish necessarily. There is an introductory section, but because of the modular aspect, it allows each particular site to determine how to best lay it out based on their physical plant and how things are set up. So we’ve had it exhibited in historic sites, museums, barns, libraries, historic houses, just a little bit of everything. And depending on the location, that same exact exhibit that comes to us from the Smithsonian would look very differently. So sometimes it might be just a straightforward linear setup where people can go from A to B to C. In other situations we’ve had it set up where it’s in multiple rooms. We’ve had it actually in multiple situations where the host partner that we’re working collaboratively with is too small, again, because these are mostly in rural communities and they’re not very large institutions per se, so the host partner works with another collaborator and it’s actually hosted off-site at that. So most recently we had it at the Oxford Museum here, which is a very small museum on the eastern shore of Maryland, and it was hosted at a former historic church that’s been used as a community for public education programming.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah, I visited the one in the church in Oxford. It’s always just the cutest little rural church in this beautiful old town. And I remember there was like local art and some other really cool local stuff as well. And it was just, yeah, it was a beautiful space to take in an exhibition.

Rob Forloney: Yeah, it’s been wonderful. I mean, we’ve had a wide variety of different organizations. As I said, we had it in Sumner Hall. The Way We Worked exhibit was there at the Grand Army of the Republic Hall, which focused on African-American veterans from the Civil War, we’ve had it at the Calvert Library System. We’ve worked with colleges and universities quite a bit as well, so Salisbury University and Frostburg also have had them. It really runs the gamut of the types of sites that have been able to participate in the program, so it’s not just your typical museum per se, but lots of

Hannah Hethmon: And I remember you telling me there was one that was installed on a ferry…

Rob Forloney: That was one of the pop-up exhibitions. Exactly. So what’s really interesting about it, as I said, is the pop-up exhibits, what I love about them is it really allows for a lot more creativity and flexibility than your traditional museum exhibition. And because of that, we see a wide diversity of ways that the exhibits manifest. And with the Oxford Museum, they have an exhibit tied to waterways. And the idea behind this was they wanted to talk about resilience and climate change, water level rise in the community. So they worked with a local artist and he did an art installation in the church around the Smithsonian’s exhibit where you could look at examples of fine art tied to what the community might look like in the future based on you know, sea level rise. So they were landscapes with houses and then poured clear resin showing what would happen with sea level rise and how high the water would come up.

But in addition to that, there was a number of different installations set up around town. So on the water by the ferry, which crosses the river, there was information about waterways in the Museum on Main Street program and a lot of specific information about the relationship of the transition from land to water. Once the exhibit was put in place, they created an exhibition about the ferry itself. It’s one of the oldest, I think might be the oldest continuous working ferry in the country going from Oxford to Bellevue. And what they did is they put together interpretive panels on the ferry itself. That way people who are traveling across the ferry would be able to learn about waterways. They’d be able to learn about the Museum on Main Street exhibit and the local history while they were actually traveling on the boat. The exhibit is still there. So it’s designed as a pop-up exhibition, a temporary space, but because it was so popular, the ferry has continued to use it and it’s still on display today.

Hannah Hethmon: I love an interpretive panel in a practical spot as you’re like just moving through a space. I was picking up someone, a visitor from England from Dulles airport, and I was trying to remember the history of the airport’s design and everything as we’re walking and then boom, we’re walking out and there’s this great exhibit panel just on the wall on your exit.

So it was such a wonderful moment to be able to like grab that history and share it with that person and yeah, have a little, add a little museum-y experience to something very rote like picking someone up from the airport. And I can imagine the fairy is kind of the same way.

Rob Forloney: Exactly. I mean, I think that’s why these pop-up exhibitions are so popular because they provide a combination of educational, social, experiential, and overall enjoyable qualities in spaces that are atypical. So people come across them or they’re really done in a way that’s much more as immersive and participatory than you would typically get in a lot of these other small historic houses or rural museums as well. So it allows for this flexibility and creativity that you don’t necessarily have when you’re designing an exhibition that’s going to be long-term.

Hannah Hethmon: And this the dynamic of—now some of I know the Museum on Main Street people are coming to see the exhibition But then some of the elements that go with it and other pop-ups beyond the program, you’re putting them in a space where people aren’t intentionally going to seek out an experience like this and then they encounter it. And so that’s a whole different design a whole different type of experience when you encounter information, when you encounter this engagement rather than going and seeking it out.

Rob Forloney: Yeah, I think those are two other qualities that are really important about pop-up exhibitions. They provide opportunities to engage audiences in unusual places. For example, when we did The Way We Worked, focusing on occupation, in Sumner Hall, we had 92 or 93 different exhibits and programs spread throughout Kent County. Twelve different museums were involved. We had the school system [and] all of these different places where people could go to see and learn about occupation in the area and in the region, but in places that you wouldn’t expect. So even the local tractor company got involved where you could go and purchase new equipment, but they actually created an exhibit of all historic tractors on their property. And it really provides a unique opportunity, I think, for museums and historic sites to engage people beyond their walls. So as part of that, they’re really innovative and using new ideas to engage those audiences.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah, I think on that note, this is kind of a similar question or topic, but I was thinking about how Maryland is kind of an interesting example of this, because obviously, Museum on Main Street goes to all the states, I think, and Guam, so they go to places where there aren’t the national Smithsonian museums. But people who might not live in Maryland might think, Maryland’s a small state, why can’t people just go to the Smithsonian? Why can’t they go to Baltimore, Annapolis, the [National] Mall?

Can you talk about that distance between even you know Western Maryland, Eastern Maryland and the Smithsonian and what a difference it makes to take things out to people in their town?

Rob Forloney: Yeah, so there’s a couple of different things that are important about that. One, I think people—geographically on the map, it might look like we’re in close proximity to the Smithsonian in Washington DC, but in reality when you try to drive from the mountains of Western Maryland or if you’re in Worcester County or Somerset County by the Atlantic Ocean, it takes a good deal of time to go from place to place. So that’s one issue is it’s not as close it actually looks. If you’re living in the capital region and you’re not too far outside of DC in the suburbs there in like Montgomery County or Prince George’s County, that’s one thing. So in the proximity, it’s an issue, I think, just in terms of getting people engaged.

But as I said, the other thing that’s really crucial about this is it’s focusing on the local community, the stories of that particular region and those people. So though we have the national exhibit and it helps raise the visibility of the organization see the Smithsonian name, they hear about Maryland Humanities coming, so a lot of people get interested in that. They’re creating exhibits and programs that are really unique to that particular place, and they can fine-tune things based on the stories that they’re telling. So a lot of the work that’s taking place is creating these networks and providing the opportunity for outreach.

One of the things I think that’s really most crucial about Museum on Main Street is we view it as capacity building as well. So the exhibit is there on site typically for six weeks. However, we do a tremendous amount of work before and after providing support to these communities to help build up their capacity. So after the exhibit is down, they have a new toolkit to pull from and they’re able to go into their community and continue developing exhibitions, working on programs and really building out those dynamics in the partnerships that they’ve developed over time.

So the capacity building for me in particular is one of the things that’s most exciting about the Museum on Main Street program is that we’re going out and using our resources, our skills and also pulling in outside consultants and experts as part of this process too.

So when building the program, they can pick and choose different things. We have like a whole menu, an a la carte menu of things that they’re interested in. So if they’re really interested in social media, we can have them work with someone who’s focusing on that. If they’re interested in grant writing and management, we can bring in a consultant or expert who focuses on that. Other times we’ll bring the entire team together, like we did recently with Dr. Julie Rose, and she talked about difficult histories from the book that she’s recently written and gave or I started off as a consultant myself on the Museum on Main Street program, and I would do a lot of work about community engagement, listening, shared authority, and teaching the organizations how to work collaboratively with the community. So our capacity building is a major part of the initiative outside of just having the exhibit and the programs on site for that six weeks.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah, I think you described it when we were talking previously as like kind of a catalyst for so much more in the community.

Rob Forloney: That’s right.

Hannah Hethmon (Narration): We’ll be right back to my conversation with Rob Forloney, but first it’s time for a digital minute with Amanda Dyer, Creative Director at Landslide Creative.

Amanda Dyer: Hi, I’m Amanda Dyer, Creative Director at Landslide Creative, and I’ve got a quick tip you can use to improve your museum website. Think of your website visitors as skimmers, swimmers, and divers skimmers. Wanna get in, get the information they need, and get out as quickly as possible. Swimmers might be willing to spend a bit more time and are looking for content that piques their interest and divers wanna explore and take it all in.

Consider each of these types of visitors in the website experience just like you would in your museum. For skimmers, make sure the most important information can be found quickly and easily. For swimmers, think about how you can use interactive content and media to encourage engagement and for divers, offer more in-depth resources, and regularly add fresh content.

You can learn more about how to design for skimmers, swimmers, and divers on our website at landsidecreative.com/skim

Hannah Hethmon (Narration): And back to the episode.

Hannah Hethmon: I think it is also connected to this, you know, this distance question. I think there’s this question—anywhere in the country—of well of course people are going to go to the city for their culture. And I love cities I love city culture, but you can experience culture and create culture and have as rich of a cultural experience in your own town and community. If you choose to go to the city and visit that culture, that’s fine. But really bringing the museum out to the towns to say this is as valid a place for culture and creativity and history to continue in the long run.

Rob Forloney: Yeah, that’s exactly right. I mean, there’s such diversity and variety in the different types of cultural institutions and organizations that are throughout Maryland. Each one of these communities has a really unique story to tell, multiple stories to tell from a variety of different perspectives and viewpoints. So that’s what we’re hoping to do again, is like taking the resources and expertise and technical assistance that we have and then providing and building upon that to improve the work that can happen in these rural areas as well. And again, creating a network so they understand what else is happening because so much of our work I think happens in isolation often, especially with smaller institutions.

The organizations we’re working with have very small staff, sometimes they’re entirely volunteer-run run and they just don’t know what’s happening in the field. So we provide the support structure and convene the conversation so they understand what else is happening and they can work collaboratively as a group. So that’s one thing that’s nice about the cohort. When we do our Museum on Main Street program, we’ll typically have five or six different communities that we’re working with and we have them come together for conversations and discussions and training. They brainstorm ideas about what they can do and we even do that at the national level too.

So I recently went to the planning for Spark!, which is the next exhibit that the Smithsonian just created, and cites organized different program officers from around the country to come together. So there are people like myself, people from Wyoming, South Dakota, South Carolina, and we’re all having conversations about like what we could do, what we’re planning on doing, and sharing our creativity and ideas with one another so we could improve the programs at our state level too.

Hannah Hethmon: And I think what’s interesting, especially about Spark, is that it’s not a one-way street. The exhibition itself is created from these amazing stories of innovation and creativity that have come out of small towns. And then the exhibition with these stories is gonna go back into small towns who are then gonna add to it and talk to it. And I know Museum on Main Street collects a lot of audio stories as well and content that comes back and enriches their understanding them to create better exhibitions and to have a Smithsonian that’s more representative of the full country. And so I think for any museum considering kind of pop-up going outside the walls this is absolutely beneficial in a two-way direction. Yeah.

Rob Forloney: Yeah, I am incredibly excited about Spark coming to Maryland. And part of it is it’s so much more about process and transformative innovations, as you said, in the communities rather than content per se. So it’s really celebrating different ideas that communities have to have an impact in people’s lives. So what we’re going to be doing is a little bit different than in the past, where we’re going to be doing a lot more capacity building and upfront work with our communities in Maryland to identify groups and different organizations and locations that are doing this type of work already and providing resources in advance. So then the companion exhibits and programs that they create what has been going on rather than the other way around where usually a site is awarded the space and then create something after the fact when it comes into the area or shortly before. So typically we’ve got planning years and then we have the tour year or years as part of that process and we’re kind of flipping things. And as you said in terms of innovation and invention one of the things that we really want to focus on is language access because we identified the fact that there’s more languages being spoken throughout Maryland and too often we aren’t providing opportunities for people to engage in the exhibits and programs in that way. So part of the idea with Spark is we’re hoping to add languages as it travels across the country. It’s automatically going to have a tremendous amount of Spanish built into it in the interpretive labels as well as some of the technology and then some of the games and interactives have Spanish components as well but the hope is that we can add Hindi, Mandarin, there’s talk of adding Lakota. I’ve spoken with some people here about additional languages that we could add in Maryland, so it really makes it much more inclusive and accessible to the population in that way.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah, I think you said Algonquin is one of the Native languages spoken in Maryland, right?

Rob Forloney: Exactly. We have a number of Indigenous communities that speak Algonquin and a number of state-recognized tribes who are part of the process. So it would be wonderful if we could add Algonquin into that.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah, awesome. Well, I thought we’d talk about some examples outside of Museum on Main Street. I know the two that we talked about before in Maryland are at the Baltimore Museum of Industry and then in DC is the Anacostia Community Museum. Do you have any thoughts on what the Baltimore Museum of Industry did with their outdoor exhibition? Because I think that’s kind of a fun example as well.

Rob Forloney: For me, I think of it, I’m an artist also, and I think about the difference between doing an oil painting versus doing a sketch. And when we as museum curators and exhibit designers are putting together a long-term exhibition, we tend to be much more constrained and restricted about what we do, because we know it’s going to be there for seven or 10 or 15 years, and we want it to last. So a lot of time, a lot of money and resources go into it. And because of that, you don’t have the same level of flexibility and creativity that you have if you’re doing a pop-up exhibition. It’s like a sketch. It’s something that you can do really quickly. You can experiment. So I think it really allows the opportunity for institutions to be outside-of-the-box thinkers in many respects. And in addition to that, I think COVID caused organizations to engage in pop-up exhibits in a different way. They were forced to do this.

So with the Baltimore Museum of Industry, what they did that was really wonderful was they were working on an exhibit focusing on steel, Bethlehem steel in Baltimore and the steel workers there. And as part of this process, you know, the pandemic hit and everyone was drastically impacted. This is an understatement, but as museums, we closed down our interior spaces. Everyone shut down and you couldn’t communicate or connect with visitors in the same way. What the Baltimore Museum of Industry did was they used the fence along the key highway and they put the exhibit, all the interpretive panels on the fence itself. So people were able to go and see and participate and understand the stories of what they had done. It was called Women in Steel, and it went up in the fall of 2020, so when everything was still closed to the public. And they also worked collaboratively with Aaron [Henkin], who deals with a lot of local public radio here, WYPR.

Hannah (Narration): Correction, Aaron *Henkin* is the radio producer they worked with.

And he created podcasts as well, talking with some of these women who are working in the steel mills and also the surrounding Sparrow Point area as part of that process.

Hannah Hethmon: Such a good podcast. Everyone should go listen to Sparrows Point: An American Steel Story. I’ll put it in the show notes. Everyone should listen to that podcast.

Rob Forloney: So I think that was a great way of really looking at it and being forced outside of the box. Also, I think a lot of this work, as I said, is happening all the time. The Smithsonian Folklife Festival does this every year on the National Mall. You mentioned the National Mall before. This is a common area where people from all over the country and internationally gather on a regular basis. And because of the nature of the space, you can’t have anything permanent. The National Park Service, and I do love them, won’t allow anything to happen in a very substantial way. So everything is very ephemeral, and it’s designed to be ephemeral in the space itself. But the Smithsonian has been putting together this festival for decades now.

and every year they do something that’s unique, that’s different, that’s celebrating living cultures, and it’s only there for two weeks in July around the 4th. In the past, they’ve done things like having people from Peru come and Quechua speakers designing through vines the actual bridges that they use to transverse the wide chasms in the Andes, or the Dogon people designing mud huts as part of the process. And again, these are, by design, made to be temporary. But they engage people because they’re participatory, they’re creative, they’re inventive, box thinking in terms of what we think about when people imagine a museum with a lot of display furniture, having objects behind plexiglass cases or a lot of text on the wall. You just have a lot more availability through these kind of educational and innovative ideas with pop-up exhibits.

Hannah Hethmon: One of the other things, one of the things that I was involved in during the pandemic was at the Anacostia Community Museum. And like the Baltimore Museum of Industry, they had an exhibition that was planned, Men of Change, about influential African-American men. And they decided not just to put it outside their walls, they went into a different neighborhood, the Deanwood neighborhood, another African-American neighborhood, and spread the exhibit out throughout the neighborhood at important sites so that people could walk through their neighborhood and see these pictures of not just influential African American men in the country, but local people who had made a big difference in the Deanwood neighborhood. You know, their fathers, their mentors, the people that they knew, their grandparents. And I had a small part in helping to edit the audio tour that went along with it. You could go and stop at each stop and listen to stories from locals people as well. And that was really cool because the museum not just got outside their walls, but even went outside their immediate space around the museum.

Rob Forloney: And again it really activates the entire community. So it’s not just about the site, not just about the museum or the cultural institution anymore, it’s about the people and you’re feeling, you’re empowering them and making them get a sense of the fact that they’re in control and there’s ownership, this co-curation and authority by being part of that process.

One of the things that we did as part of the Museum on Main Street that just finished up Crossroads here in Maryland was I collaborated with Washington College faculty and students and we actually trained a lot of these small organizations on how to design their own pop-up exhibits. So we create a series of workshops over a sequential period of time where they learn specifically how to actually identify the different target audiences, develop the narratives, but then we also taught them the techniques of what you needed to do with hands-on workshops. So we had sequential workshops over time where they came in early on developing their story and then coming back after they had worked on it for a bit to actually digitize the images and objects from their collections, 3D pieces. We also taught them how to use Canva. And then we had eight different museum groups or community groups create exhibits in their windows with the interpretive panels about different stories that were unique to them.

And then part of the major Chestertown Tea Party that they have each year where tens of thousands of people come into Chestertown, all of these community members had these interpretive panels in their windows as part of the pop-up display.

Hannah Hethmon: I think this episode should be called, Pop-Up Power, Power of the Pop-Up. There’s so much potential. I hope everyone who’s listening is inspired because I’m like, we need to do more pop-ups. I’m all riled up.

Rob Forloney: Well, the other thing, I think there’s just a level of play here. As I said, it’s enjoyable and it allows you to do things that you wouldn’t otherwise do if you were creating a permanent exhibition. So people tend to be much more interactive, and participatory. They’re more equitable in terms of including voices or community groups that they wouldn’t work with before. It attracts new audiences, so people who wouldn’t think about going to your site by having a pop-up exhibit like this off-site, you’re pulling in people and letting them know what you’re doing in a way that you couldn’t do otherwise. So it’s just a great way of really being experiential, flexible and creative.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah, I think there’s a great example from the Spark! exhibition, the Museum on Main Street, one of the stories in there is about Bethel, Vermont. And I think this captures both like just silliness and play and innovation. They had like a whiteboard out or, you know, a flipboard where people could write ideas for the town. They were having, you know, an event and someone wrote, “BU.” And they were just like, yeah, that’s Bethel University. OK, hey, town, would you like to do Bethel University? And they offered it up to the town as one of the options of things they could all try. And they’re all like, yeah, why not? So they created this like one-month community university where everyone came and taught a class kind of like that movie Acceptance.

Rob Forloney: It’s all about lifelong learning. Exactly. Everyone in the community thought about what they could contribute and how they were able to give back and it just created such a sense of goodwill and citizenship within that community. I think it’s great. That story in Bethel is really inspiring.

Hannah Hethmon: I think that’s the power of that play and possibility and ephemerality that pop-up exhibitions can bring to spaces. Well, thank you so much for coming on the podcast and sharing some of the cool stories from Museum on Main Street.

Rob Forloney: Happy to do so.

Hannah Hethmon (Narration): Thanks for listening to We the Museum. You’ve been listening to my conversation with Rob Forloney, Program Officer for Partnerships at Maryland Humanities.

To learn more about the Smithsonian’s Museum on Main Street program, visit Museumonmainstreet.org. Again, their podcast—produced and hosted by me— is called Smithsonian’s Stories from Main Street.

To learn more about Maryland Humanities, visit their website at MDhumanities.org

The podcast from Baltimore Museum of Industry we mentioned is Sparrow’s Point: An American Steel Story. You can also hear more about that museum’s great work in episode five of We the Museum, which is about collaborating with public schools to honor food service workers.

I’ll leave links to all these resources and more plus a transcript on the show notes page for this episode at wethemuseum.com.

Once again, a big thank you to our show sponsor, Landslide Creative. Making a podcast takes a lot of time and energy, and I wouldn’t be able to set aside the space to make this show without Landslide Creative’s financial support. If your museum is considering a new website, definitely make Landslide Creative your first stop.

Finally, I’ve been your host, Hannah Hethmon.