Episode 1

Community Curation and Digitization at the NMAAHC (with Dr. Doretha Williams)

Show Sponsor

Landslide Creative provides custom website design and development for museums who want to increase their engagement and connect with their visitors, donors, and volunteers. Stop fighting with your website and focus on growing your impact. Visit LandslideCreative.com to learn more.

Show Notes

About the Episode

From day one, the National Museum of African American History and Culture has made it a priority to support Black history organizations and family historians around the country, not just in D.C. In this episode, I’m joined by Dr. Doretha Williams, who leads the museum’s Smith Center. I wanted to hear more about their community curation and digitization programs, where they travel to cities around the country and offer no-strings-attached digitization and research support to institutions and individuals. Hear about the community-building that goes into every visit and find out what other museums and history organizations can learn from the NMAAHC’s approach.

About our Guest

Dr. Doretha Williams is the Center Director, The Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History (Smith Center) National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution. The Robert F. Smith Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History (Smith Center) at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) serves as the burgeoning digital humanities and public history forum for the NMAAHC. The Smith Center’s mission is to make historical collections accessible through digitization, public programming and interaction, and to support educational development in the museum and archives fields. Through the Community Curation Project, Professional Curation Program, Interns and Fellowships opportunities and the Explore Your Family History Center, the Smith Center serves as a major public outreach component for NMAAHC. Dr. Williams received her degrees from the University of Kansas and Fisk University.

Links

- NMAAHC Smith Center

- The Community Curation Program

- Press Release: National Museum of African American History and Culture Uplifts Visitors’ Voices With September Programming

Media

Transcript

Hannah Hethmon (Narration): Hello hello hello. Welcome to the very first episode of We the Museum: a podcast for museum workers. I’m your host, Hannah Hethmon, Owner and Executive Producer at Better Lemon Creative Audio, where I make podcasts for museums, history organizations, and other cultural nonprofits.

In this show, I’ll be speaking to museum workers in the US and beyond, exploring ideas, programs, and exhibitions that inform and inspire. This means everything from digitization and collections management to unionization and decolonization. I’m hoping to create a space where we can slow down and take a moment away from the day-to-day work to learn, grow, and expand our toolkit.

In this inaugural episode, we’re kicking things o with a really special guest from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.. Dr. Doretha Williams is the Center Director of the museums’ Robert F. Smith Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History. The Smith Center is the digital humanities and public history forum for the NMAAHC. They focus on making historical collections accessible through digitization, public programming and interaction. They work with Black history institutions around the country and directly with members of the public researching and preserving their own family history.

The Smith Center’s traveling work got started in 2017, meaning they really only had a few years before the pandemic disruption. In fall 2022, they finally got back out on the road. I figured this grand re-launch was a great chance to learn more about what they do and how they do it.

In our conversation, Dr. Williams shares a behind-the-scenes look at everything that goes into a community curation city visit, how the pandemic forced them to reenvision what they do, and what other museums and public history institutions can learn from their approach.

But before we jump into our interview, I want to shout out our show sponsor, Landslide Creative. This podcast would not be happening without their support. Landslide Creative provides custom website design and development for museums who want to increase their engagement and connect with their visitors, donors and volunteers. With a custom website designed for the unique needs of your museum, you can stop fighting with your website and focus on growing your impact. Head over to LandslideCreative.com to learn more.

So what does is look like when the Smith Fund Digitization truck pulls in a city? And what’s the experience like for sta and community members?

Dr. Doretha Williams: Well, first and foremost, our team works with individuals, families, and institutions prior to that even happening. We spend a year visiting a place before we even drive the truck or set up or anything like that, because the goal of this project is always to nurture relationships with institutions, communities, and families. And that can only be done with multiple visits and really just getting rooted in those communities. For example, our community curation in Chicago in 2019. We spent late 2017 and most of 2018 going back and forth to Chicago and meeting with our partners there. And we worked with the Black Metropolis Research Consortium in Chicago. And mainly they do the work of preserving the history of Black families and Black institutions there in Chicago.

And the Du Sable African American History Museum is one of the lead members of that organization as well as the Chicago State and Shorefront Legacy, which is a collecting organization in Evanston, Illinois. So we spent over a year—maybe a week out of every month for a year—ust going back and forth, really immersing ourselves in Chicago. And we do that at every site. And then we spent six weeks in Chicago. So it’s not just a, we drive up and start this work, we actually just get so involved in, within the, with the organizations and the families. And we do so in a way that just becomes hilarious. We also did one in Denver in 2018, and, you know, by the time we actually launched the community curation, we had our own badges for the Blair Caldwell African American Research Library. And they would call us on the PA system. We had just become part of their sta. It’s really about relationships, first and foremost.

But when we do get it together and we, we, we get ourselves settled—our team is between 10 and 15 strong at any given time—and we do have an amazing mobile truck that holds all of our media equipment. And then we have our flat item equipment as well, that’s normally set up in our host institution.

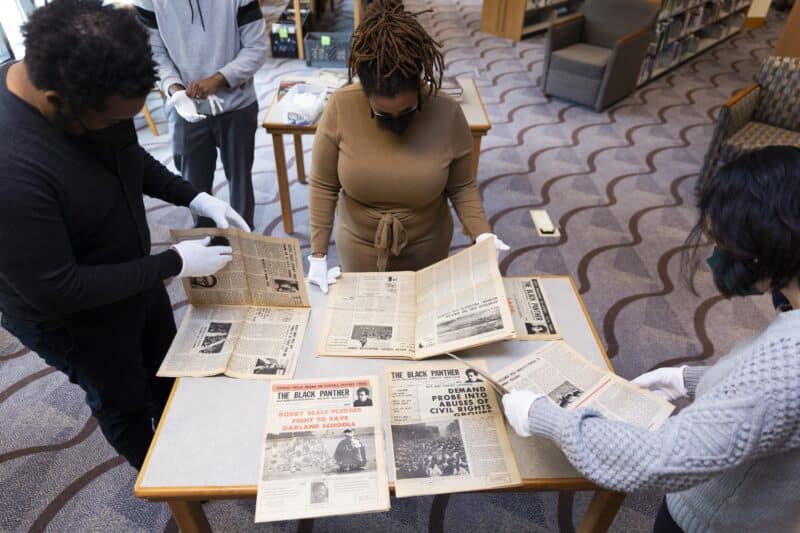

And basically what we do is we are open to—at least for the first three, Baltimore, Denver, and Chicago— we’re open to the public and we work with the institutions. And what happens is there’s usually a call out, social media, the paper, the Chicago Defender, Tribune, all of those platforms. People are able to go online and sign up to have their items digitized. And we specialize in two main forms: flat and moving. And so that’s all your VHS reel to real film, cassette tapes, audio, for your moving images. And then for flat items, that’s photographs, that’s paper, any, anything that can be placed on a photo stand and, and digitized in that way. Each and every individual and family, they get all of their material back and they get a cute little thumb drive with their material digitized.

And that is that, if that is the end of the conversation. We also are always prepared for families who want to see their material in the museum. And so that is a second step. We make sure that families know that nothing is kept if it’s not something they want us to have. But we do always have paperwork there to start that conversation, because families do like to see their family videos played in the museum. And when they do that, it does go into our collection and is used for various things, educational purposes. There have been movies and documentaries as well. And people can go to the second floor—this is prior to the Pandemic—but we play those family movies. And people can go online to the Smithsonians archive and pull those images.

So we make sure that families feel safe. The material that we’re digitizing goes back to the families. It will never show up unless there’s an assigned release form. And even then, we’ll let you know when it happens. If, you know, someone is making a documentary, comes through and wants images of Denver or Chicago, and that image or video fits, we’ll reach out to those families.

So we normally park that beautiful truck in front of our host institution and do that great work. And I tell you, it is the most rewarding experience I’ve ever had professionally. because people come in and they want to tell their family story. They want us to digitize their family histories. In 2018, when we were in Denver a gentleman came through Mr. John Gray, and he had these totes that he hadn’t been through, that he’d pulled them from his parents’ house, the house he grew up in. It’d been years his parents had been, had passed for some years, from decades I do believe. And he opened them up and we were just waiting, you know, for him to go through ’em. And he was like, please, you know, go through these with me. And so our sta was going through some of the most intimate things that, you know, that someone can hold from their parents. And he just gets excited and he pulls out the bundle of letters and their correspondence from his parents, family members, cousins, uncles, all over the world.

And we were able to digitize those for him, but he allowed us to read them. You know, so there’s a certain amount of trust that people give to us. And so we have to maintain that. And that’s one thing that I always speak to when it comes to leadership at the Smithsonian or our museum is we have to maintain this trust and I do whatever we have to do to maintain that trust. I’ve also changed ways that we’ve done things just because things, you know, may not seem trustworthy. So we make sure that that is incorporated.

So we’re normally there for a month to six weeks, and we become family. When we were in Denver, we had a family adopt us, and they open up their home for dinner, bring us food at night. Cause we were there so late at night and you guys want some Chick-fil-A, you want this or that? But we’ve had some of the most amazing experiences with community curation.

Hannah Hethmon: If you have a few more anecdotes of the people that you spoke to and interacted with and what that looked like?

Dr. Doretha Williams: Yeah. The greatest thing is the intergenerational conversations that happened. In Chicago, it was both what we wanted to develop as well as organic. Families, a lot of times the younger family members know of the event, but they don’t hold the photos. Right. Or they don’t have the VHS tapes because ask a 20-year-old, you know, where they keep their VHS tapes, they don’t have them, you know. So it becomes a thing where we go, we go to grandma’s house, we go to Auntie’s house, and we talk about those pictures, and they bring them in. And oftentimes it’s grandmother, mother, and grandchild together bringing those items in to have them digitized. And, you know, the grandchild is asking, who is this person? Who is that person? And grandma is, is telling them that their history.

We had a woman come in with a very tattered late 19th-century photo. And it was we, what we did is our Leah Jones, who’s our photographer, did a digital stitching for that. So that, oh my goodness. All of those rips and tears that were, that were on the actual photo once digitized, you could not see. She put the photo back together. And while we’re there, we were asking her who this person is, and she was giving us what she knew. We also have our genealogy team who was with us at the time, on site Camilla [S]. And she opened up her laptop and said, let’s find who this person is. And by the time we had digitized the photo, we had also found the full name of this woman who turned out to be a great-grand of so many, so many generations. And the mother was able to turn to her daughter and say, this is your great-great grandmother. And she’s just beaming. And you could see they looked all alike. Like you could see that, you know, things like that have happened.

You know, working with Mr. Gray, we continued conversations with him. And I’ve done several Aoom interviews with his entire family because they hadn’t really had a family reunion. And so we came together and because of the work that we digitized, brought them all together to do a family reunion. And some of the people who were mentioned, or their family members or ancestors were mentioned in those correspondence, they came to those conversations. And there was one cousin who had never met anyone on the call, but had been mentioned. Oh, they’re like, oh, I remember auntie and I remember uncle. So it’s just amazing. It’s just amazing the experiences that we’ve had and the way that we’ve helped support the institutions as well.

When we were in Chicago, we digitized some footage that had just been lost. We had footage of Martin Luther King walking before one of the marches

Hannah Hethmon: —just from someone’s home video?

Dr. Doretha Wiliams: From home video. It was actually stored at the museum. And it’s got Coretta Scott King is in it as well. They’re very young, they’re very youthful looking. And it’s also Andrew Young is in there and John Lewis as young people. But it had never been seen, it had not been preserved, and they no longer had the equipment to, to be able to see that. So things like that happen as well. We’ve just had so many great experiences and we’ve just, just came from New Orleans and that’s, that’s post pandemic. So we could talk about that if you’d like to now.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah. I wanted to ask, so the pandemic hits. You you’ve had, I guess you started in 2017, even with all the work you’re doing workshops, you don’t have that long to really have this program going. So how have you kept the community aspect alive during the pandemic with the museum doors shuttered with the vans parked back home? How have things kept, how has the program been kept alive?

Dr. Doretha Williams: Yeah. Well, we have what we call the Community Curation platform, and that is communitycuration.org. And what people can do is go online and upload their family stories, excuse me, upload their experiences and their life. And what we did is we actually promoted it throughout the pandemic. And we said, what is your experience during this time? How have you dealt with Covid? How have you dealt with quarantine? How have you dealt with the uprisings and, and and the murder of George Floyd and protests? How have you dealt with this? And people responded so strongly to that request. And you can go on to that site now and see those responses. So the greatest thing that we could do was to have a nimble pivot to say, we have to continue to engage our communities. How do we do it during the most dicult time ever for most people to ever experience it? And so that was one of the main ways we kept up with our communities: oering that platform, which we had been using for three years, but not in this way. And so we continue to send out prompts throughout the pandemic to respond. And that platform has grown tremendously for that.

We also took our Family History Center sessions virtual. They had already been working virtually with some individuals with individual Zoom sessions. But the sessions that they do where they actually support people doing their family history on platforms like Family Search going through Census Records and what have you, that went 100% virtual.

Hannah Hethmon: You can get one-on-one, people can get one-on-one help with that genealogy research?

Dr. Doretha Wiliams: Yes.

Hannah Hethmon: That’s amazing.

Dr. Doretha Wiliams: And by the time the pandemic came along, we had put together a pretty good following of people. So, you know, a lot of people had been, been with us for a very long time. And so several of those sessions that were now virtual were, you know, getting people beyond 1870, you know, getting people to find military records or deeds or wills and what have you. So that went completely virtual and actually broadened our audience because you didn’t have to be on-site right at the museum to do that work. You

could log on all of our programming went virtual as well. And we continued programming when it came to preserving history preserving your photos, talking about DNA.

The Family History Center team does a lot of work on regional studies: Black life in North Carolina, Black life in the South. We just recently did one on Texas colonies after the Civil War, and so that’s on there as well. So we went virtual. As far as the digitization services, we did have to pause that, of course, because that was in-person things that we couldn’t do. But what I did is with the team, I took the time to revision what that looks like and how we work. And there were some policies and procedures that we changed to be so, be more supportive and to be more equitable. And to make sure our work, what we did was not extractive or in any type of way seeming disingenuous.

Hannah Hethmon: Are you able to share any examples of that?

Dr. Doretha Wiliams: Of that? Yeah. So one of the projects we did what we call Professional Curation. And you know, on paper it looks really great. But what we, what we saw was individuals and families and institutions needing that cloud storage and that space to be able to store what’s been digitized. And so we were asking institutions to be prepared for something they couldn’t really handle at the time. And so what we decided to do was make all of the curation programs look like community curation. And then whatever happens once the projects are done, whether it’s shared ownership or asessioning happens post project. And that really helps institutions, number one, to be empowered with their own work and be empowered to have ownership of their own collections and their own history and narratives of their existence as institutions and as communities.

So we did, we made that shift. And so that’s what we do now. Everything is service-based in the beginning. And if that’s the end of the conversation, that’s the end of the conversation. Whatever happens when it comes to shared ownership or usage on our website is post the conclusion of that project. So this allows us to be more holistic in the work that we do. We’re able to digitize more of collections. We’re able to build relationships.

We also instituted our equipment gifting program that we’re gonna be launching, that we’ve, we have the, our pilot sites for that right now. and that includes the Black Metropolis Research Consortium specifically the Shorefront Shorefront Legacy collecting, the Blair Caldwell African American Research Library Denver, Morgan State University, our historically Black college and university representative in Baltimore, and the 18th and Vine Historic Jazz district in Kansas City, Missouri. So those are the sites that will receive equipment so that they can do their own work. Because one thing that the pandemic taught us is we can’t be everywhere that we want to be. And during a time when we were needed so desperately, we couldn’t be there. Hmm. And so we were able to rethink what that looks like. And so we’ve made our visits, we know how we’re managing it. And those items will be delivered sometime Spring 2023.

Hannah Hethmon: And are those for them to just for digitizing their own internal collections, or also to do the community work as well?

Dr. Doretha Williams: It depends. What we were able to do is define what the site will do with the equipment. So with the 18th and Vine, it’s a collection of institutions. It’s the American Jazz Museum which is also Smithsonian aliate. It’s the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, which is heavily tied to major League Baseball, and then the Black Archives of Mid America. So what that allows them to do as collectively to digitize their material. So that is their first and foremost task is to make sure that the institutions in that district have the equipment and to preserve their material. The Jazz Museum has one of the largest jazz film collections there; the John Baker Film Collection is there. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum has some ledgers from 1920 from the founder of the Negro Leagues and the games that were played, and the money that the players earned. The Black Archives of Mid America holds a great collection of self-produced videos that they did back in the eighties called Black Archives Presents. So those are some of the lead collections that they’ll be digitizing.

Now for the library places. We, they will be digitizing their own work as well as putting together ways to be places for public to come digitize as well. That’s part of a public libraries mandate. And so we try to figure out how that works as well for the HBCU site that is our museum’s platform to support historically Black colleges and universities. So that’s where that representation comes, and that is to make sure that those collections are digitized as well. So each site is, we’re calling a hub, and each hub is defined dierently depending on how they interact with one another and their communities.

[Musical transition to sponsor break]

Hannah Hethmon [Narration]: We’ll be right back to my conversation with Dr. Williams, but first, it’s time for a digital minute with Amanda Dyer, Creative Director at Landslide Creative:

Hannah Hethmon [Narration]: Now back to the episode.

Hannah Hethmon: It’s just so much going on. Even more than I realize doing my research and reading up on things. I think if any institution could show up and ask for stu and just get away with it, it would be the Smithsonian, right. You have the power, the authority, the credibility, but it sounds like it’s just an incredibly give and provide services and then, and then from there collect. Yes. And I think a lot of museums could learn from that, museums who couldn’t get away with just asking, but who do anyway, could learn from this focus. So I wanna kind of shift to that: applying this elsewhere. You’ve highlighted some things. What do you think is innovative and what do you think that other institutions can take from this, even without the wealth of resources and scope that the Smithsonian has?

Dr. Doretha Williams: I think one great thing that I’ve done with the team and what we acknowledge because we all come from smaller institutions, you know, we weren’t like born and raised in the Smithsonian, we all came from smaller places, is that this has already been happening. So, one thing that I try to do when we go into the communities, it’s number one, support what’s already going on the ground. What we do not do is to go into communities and say what needs to be done and how it needs and how it needs to be done. It’s just not something we feel is our role. So whenever we are in a community, we’re supporting what is already being done and what needs to be done. And then we take it from there. That’s very important. So part of that whole visiting for that year prior to, is to figure out what those needs are and to support with that.

If you’re in a small organization, it’s hard to keep the lights on, it’s hard to keep the collection, it’s hard to do public programming and to be there for your communities. So one thing that we like to do is to be that undergirding support. So the work that we do, and like we, we were just in New Orleans and we worked with Dillard University, HBCU in New Orleans, and we sat up our equipment there and we digitized several collections while we were there, all while the existing sta ran the library. Because what? They have a library to run, who has time to buy and purchase and set up all this equipment? We do. That’s what we do. We like to travel and do this work. It’s very important. But you can’t take a library that has a sta of three and tell them they need to preserve their collections and run the library and deal with students and do these things. So I think that one thing that we try to do is to provide that support. We are not directing anything or telling anyone what to do. We are there, you know, to support and be of service. So you know, finding those things, those, those that equipment or that smaller technology that people can do to preserve, having institutions, having those programs, which, you know, everyone already does all this, this great work. We definitely haven’t invented anything new, but just making sure people are open to having those conversations and preserving that history.

Hannah Hethmon: Yeah. It sounds like there’s a lot of interinstitutional collaboration as well. Yes. between small and big. And if you have the resources as a larger institution, are you sharing the wealth? Are you lifting the other organizations up? Are you empowering them to reach the communities that they may have better access to than a national institution? That’s an important question. I know a lot of large museums kind of operate as, you know, you know, a a a siloed corporation or something, you know, where it’s all about just building up internally and funneling money back in. And, you know, I love this focus on other small institutions, on community members, on being this huge hub for collaboration and for connecting probably small institutions with each other as well.

Dr. Doretha Williams: Yeah. It’s such a it’s a rewarding thing. Like we just spent our first community curation since the pandemic in New Orleans. And we had been working with New Orleans 2018, 2019 and in the beginning of 2020, and we were actually there February 2020, right before everything shut down. And so we had had this great big meeting with like 40 to 50 institutions and, and with Dillard and Xavier University, which is an also HBCU, there was Southern and Grambling, two other HBCUs in the state. So it was just a great it was so wonderful. And we got on our plane to go home. We all had, you know, all these Mardi Gras beads on our neck cuz we went at a great time, and that was it.

And it was horrible. It was really horrible. Because, you know, it had already hit New Orleans and we were there. Also New Orleans was hit very, very hard. The Black community was hit very, very hard by the pandemic, and we could not do anything about it. We could not go and be of support. There were a, you know, collections people who lost their lives during that time period that we had met.

So that was just troubling. It was so troubling. So just to be back there in October, part of it was just, I just wanna keep the commitment. I just wanna keep the promise that we’re coming back. It was quite abbreviated. We didn’t do as much with communities. We really just stuck at Dillard doing their collections and working they had several regional conferences, so we presented there and, and worked there as well. But really it was about the I impact, it was about bringing the energy back to that space. And we drove up to Grambling State after that as well. To drive up to Grambling, you gotta drive up to the back woods of Louisiana and back and forth across the Mississippi state line. And, you know, and we’re just, I’m like driving through these, these country streets. And I actually drove through, I dunno if you’re gonna leave this in here. I drove through Sunflower County and before I knew it was Sunflower County, I just felt really connected. So Sunflower County, Mississippi is where my grandparents, my grandfather was born and raised. Him and his 13 siblings.

And I was telling my colleague who was driving with me, and I was like, “Ooh, this feels dierent, this space feels real dierent.” And I saw a sunflower and the word sunflower, and I was like, are we a Sunflower County? And she was like, yes. I said, this is my, this is where my ancestors were. This is where they were enslaved and freed. And this is where their land was. And it was just an an amazing, you know, experience just personally, in addition to professionally. So getting back on the road and getting back in the communities is something that we’ve been wanting to do, but you had to find a safe way to do it. and you have to try to find a better way. It was abbreviated and we didn’t get to do the all out full call for everything like we did in Chicago, but it was still impactful. It was still a kept promise that we would get there.

Hannah Hethmon: That’s amazing. I love the personal connection. So I’m a big fan of takeaways and lessons and jumping o points. So just to wrap up, speaking to museum professionals, public history, people who are listening who wanna do good work, who wanna do work that makes this country a better place, makes the world a better place. What are the values that, and the principles and the kind of rules or best practices that you’ve learned really quickly that you just wanna like get in people’s heads and have them, like thinking about for the next week as they go about their lives?

Dr. Doretha Williams: First and foremost, do not be afraid to push back. Do not be afraid to look at policies and procedures that are inequitable, that are extractive, that are damaging to professional relationships. Do not be afraid to push back. Your integrity as a professional is more important than any policy procedure that’s in place. And that has to be done. This is the time and place to do that. We are in a space, I do believe, where you can challenge and those assumptions of what things can do. The phrase, “we’ve always done it that way” always leads up to exclusion, always leads to racism, always leads to sexism, always leads to to those who fight against gender equality. There’s nothing good that comes from the phrase, “we’ve always done it this way.” Nothing.

So always be ready to push back with policies. Always have the people at the table who need to be there. Communities need to be in those spaces. When decisions are made, the worst thing you can do is be work in a vacuum with a bunch of professionals who have no clue how to work with families, institutions, or individuals. Always have the people at the table who need to be at the table. Stand strong on your goals for your funding. Stand on it and what you believe to be true. Stand on the uses usage of that funding. Do not be afraid to push back on that as well. If you need, you know, you do what you have to do but, you know, make sure that that is equitable as, as well and to spread the wealth.

And you know, keep doing what you’re doing. Everyone’s doing great work. Everyone’s doing great work. I mean, there, there’s not a place I haven’t been that, you know, people aren’t doing fabulous things. People are doing fabulous work. They’re preserving local histories. They’re doing the best they can with their collections and working with communities. And so we are just here, largely as a Smithsonian, but specifically for the center that we run, to support what’s already going on and, and the goals of those institutions and the missions of those institutions. So stay strong, push back. The people at the table need to be at the table. Stand strong in your morals when it comes to funding.

Hannah Hethmon: I love that. Well thank you so much for being on the podcast. I think people are gonna take a lot out of this and have a lot to think about and apply to their own, their own practice.

Dr. Doretha Williams: Awesome. Awesome. I thank you so much for this opportunity. I’m grateful to use the energy that we just had coming back from New Orleans. So when you emailed me and said you wanted to have this conversation, I was like, perfect timing.

[Musical transition]

Hannah Hethmon [Narration]: Thanks for listening to We the Museum. You’ve been listening to my conversation with Dr. Doretha Williams Director for the Robert F. Smith Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

For show notes and a transcript of this episode, please visit: WeTheMuseum.com.

You can find out more about the Smith Center and their programming by visiting nmaahc.si.edu. My gratitude to Dr. Williams for taking the time to speak with me.

Once again, a big thank you to our show sponsor, Landslide Creative. Making a podcast take a lot of time and energy, and I wouldn’t be able to set aside the space to make this show without Landslide Creative’s financial support. If your museum is considering a new website, make Landslide Creative your first stop.

I’ve been your host, Hannah Hethmon. As the Owner and Executive Producer at Better Lemon Creative Audio, I help museums around the world plan, produce, and edit podcasts that advance their missions. Find out more about my work at BetterLemonaudio.com